By ATGL

Updated February 9, 2026

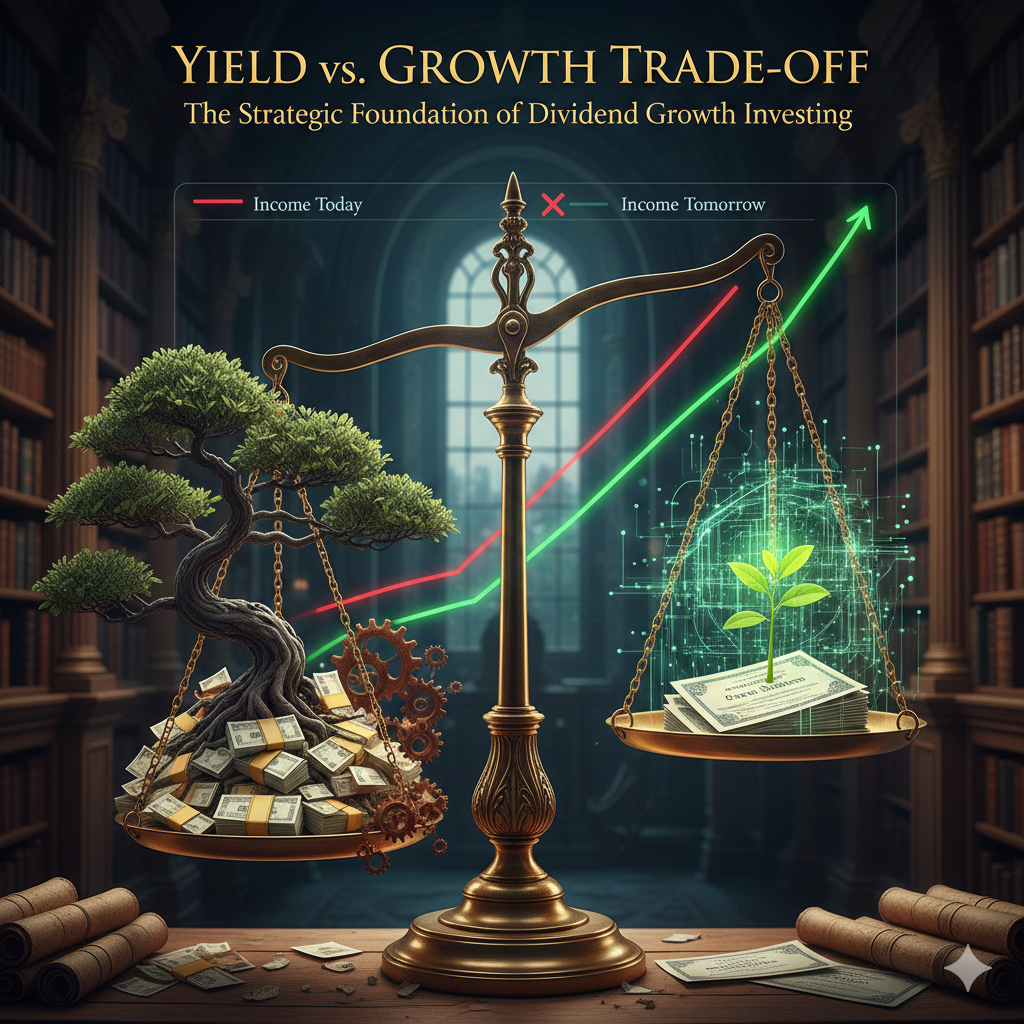

The pursuit of financial independence through the stock market often feels like a perpetual tug-of-war between the present and the future. On one side stands the allure of immediate gratification—the high-yielding security that deposits a significant check into your brokerage account today. On the other side stands the promise of exponential compounding—the low-yielding, high-growth company that reinvests its profits to become a titan of tomorrow. For the Dividend Growth Investor (DGI), navigating this tension is not merely a technical exercise; it is the definitive strategic challenge of the craft.

The “Yield vs. Growth Trade-Off” is the central axis upon which every successful dividend portfolio rotates. To understand this trade-off is to understand the mechanics of wealth creation. This article serves as the foundational pillar for the Dividend Growth Strategy, exploring why a balance between current income and future appreciation is essential for long-term success.

The Mathematical Reality of the Trade-Off

At its core, the trade-off is dictated by the laws of corporate finance. Every dollar a company earns can be utilized in a limited number of ways: it can be reinvested back into the business (Research and Development, capital expenditures, acquisitions), used to pay down debt, or returned to shareholders via dividends and buybacks.

When a company chooses to pay a high dividend yield, it is essentially signaling that it has fewer high-return internal investment opportunities. This is why we often see “Utility” or “Real Estate Investment Trust” (REIT) sectors offering yields of 5% or higher; their business models are mature, and their growth is steady but capped. Conversely, a technology firm might pay a meager 0.5% yield or no dividend at all, opting instead to pour every cent into capturing market share.

The relationship is often inverse. Generally, the higher the current yield, the lower the expected growth rate of that dividend. The lower the current yield, the more “fuel” the company has left in the tank to increase that dividend aggressively over time. This is the fundamental choice facing the investor: Do you want a large slice of a small pie today, or a small slice of a massive pie ten years from now?

The Corporate Dividend Lifecycle: Mapping the Evolution of Yield

To master the trade-off, an investor must view companies through the lens of their biological lifecycle. Every business moves through stages of maturity, and its position on the yield-growth spectrum shifts accordingly. In the “Early Growth Phase,” a company is a voracious consumer of capital. It pays no dividend because its internal rate of return on reinvestment is far higher than what an investor could achieve elsewhere.

As the company enters the “Emerging Payer” phase, it begins to generate more cash than it can effectively reinvest. It initiates a small dividend—often yielding less than 1%. This is the “sweet spot” for growth-oriented DGI investors. The payout ratio is low, and the runway for annual increases is decades long.

Eventually, the company reaches “Mature Compounder” status. It becomes a household name with a 2% to 3% yield and steady, high-single-digit growth. This is where most Dividend Aristocrats reside. Finally, the company reaches the “Legacy Cash Cow” stage. Growth has slowed to the rate of the general economy, and the company compensates investors with a high yield (4% to 6%). Understanding this lifecycle allows the investor to anticipate the trade-off. You are not just buying a yield; you are buying a company at a specific point in its evolution. The strategic goal is to populate your portfolio with companies in the middle two phases—the Emerging Payers and Mature Compounders—where the balance between current income and future growth is most potent.

The Chowder Rule: Quantifying the Compromise

To move beyond the abstract “high versus low” debate, Dividend Growth Investors utilize a specific heuristic known as the Chowder Rule. Developed by a prolific investor in the DGI community, this rule provides a numerical framework to evaluate whether the trade-off between current yield and growth is favorable.

The formula is: Current Dividend Yield + 5-Year Adjusted Dividend Growth Rate = Chowder Number.

For most stocks, a Chowder Number of 12 is the gold standard. For higher-yielding stocks (like utilities yielding 4% or more), the threshold is often lowered to 8, as the higher current income requires less growth to achieve a similar total return. This calculation forces the investor to confront the trade-off mathematically. If a stock yields a massive 8% but has a dividend growth rate of 0%, its Chowder Number is 8—acceptable for income, but potentially stagnant. Conversely, a stock yielding 1% with a 15% growth rate yields a Chowder Number of 16, signaling a powerful compounder.

This alignment allows the investor to visualize the efficient frontier of dividend investing. It prevents the psychological trap of “yield chasing” by requiring that any deficiency in yield be compensated by a proportional increase in growth, and vice versa. It turns a subjective feeling into an objective mandate.

Sector Dynamics: Why the Trade-Off is Structurally Locked

The trade-off is rarely a choice made by a management team in a vacuum; it is often a byproduct of the sector in which a company operates. Understanding these structural boundaries is essential for a diversified Dividend Growth Strategy.

In the Consumer Staples and Utilities sectors, companies operate in mature markets with predictable cash flows. Because they do not need to build a new factory every year to stay relevant, they can afford to pay out 60% to 80% of their earnings as dividends. This results in the “High Yield, Low Growth” profile. An investor seeking a 4% yield will naturally gravitate here, but they must accept that these companies rarely grow dividends at double-digit rates because their underlying markets (toothpaste, electricity, cereal) only grow at the rate of population plus inflation.

Contrast this with the Information Technology or Healthcare sectors. These companies face “existential R&D.” If a tech giant stops innovating, it disappears. Consequently, even highly profitable tech firms like Microsoft or Apple historically maintained very low yields. They prioritize “Growth” in the trade-off because the opportunity cost of paying a 5% dividend—and thus losing the lead in Artificial Intelligence or cloud computing—is too high. For the DGI investor, these sectors provide the “Low Yield, High Growth” engine that drives capital appreciation.

Recognizing these sector norms prevents an investor from “tilting” their portfolio too far in one direction. A portfolio entirely in Utilities may provide great income today but will likely fail to keep pace with a booming economy. A portfolio entirely in Tech may grow impressively but leave the investor “cash poor” when they need to pay their mortgage.

The Valuation Component: Distinguishing Opportunity from the “Yield Trap”

Navigating the trade-off requires a keen eye for valuation. In the world of dividend investing, price and yield are two sides of the same coin. When a stock’s price falls, its yield rises. This creates a psychological dilemma: is the high yield a gift from the market or a warning of impending disaster?

To solve this, we must look at Dividend Yield Theory. This theory suggests that for high-quality, stable blue-chip companies, the dividend yield tends to revert to a historical mean. If a company typically yields 3% but is currently yielding 5%, and the underlying business fundamentals (earnings, debt levels, and market share) remain intact, the stock is likely undervalued. In this scenario, the investor captures both a high current yield and the potential for capital appreciation as the price rises to bring the yield back to its 3% norm.

However, the “Yield Trap” occurs when the high yield is a result of a permanent impairment to the business. If a company’s P/E ratio is plummeting because its product is becoming obsolete, the high yield is a mirage. The dividend will eventually be cut to preserve cash, and the yield will collapse along with the share price. The foundational DGI strategist avoids this by ensuring that the “Growth” side of the equation—specifically Earnings Per Share (EPS) growth—is still positive. Without earnings growth, a high dividend is merely a return of capital, not a return on investment.

The Yield on Cost Illusion: Perception vs. Reality

As a portfolio matures, the investor will encounter the concept of Yield on Cost (YOC). This is the current dividend divided by the price you originally paid. Over twenty years, a stock bought at a 2% yield might have a YOC of 20%. While this is a wonderful psychological tool that encourages long-term holding, it can also create a dangerous illusion.

The trap lies in emotional anchoring. An investor may hold onto a stagnant company simply because they have a “30% Yield on Cost,” ignoring the fact that the company’s current yield and growth have deteriorated. From a purely rational standpoint, the price you paid ten years ago is irrelevant to the decision you make today. Every day you do not sell a stock, you are effectively “re-buying” it at the current market price.

Mastery of the trade-off means using YOC as a celebratory milestone of your past success, but never as the primary reason for your future allocation. You must always ask: “If I had this much cash today, would I buy this stock at its current yield and growth profile?” If the answer is no, the trade-off is no longer working in your favor, regardless of how high your “cost basis” yield appears to be.

The Tax Efficiency of the Trade-Off: The Hidden Cost of Yield

One of the most overlooked aspects of the Yield vs. Growth trade-off is the impact of taxation. Not all dividends are created equal, and the “drag” of taxes can significantly alter the compounding trajectory of a portfolio.

For investors holding stocks in a taxable brokerage account, high-yield stocks create a “forced realization” of income. Every time a dividend is paid, a portion is surrendered to the tax authorities (typically at the qualified dividend rate of 15% or 20%). This effectively reduces the “reinvestment power” of the portfolio. If you receive a 5% yield but pay 20% in taxes, your effective “reinvestment yield” is only 4%.

Conversely, low-yield, high-growth stocks are inherently more tax-efficient. Because a larger portion of the “Total Return” comes from capital appreciation rather than cash payments, the investor controls the timing of the tax bill. You only pay capital gains taxes when you choose to sell the shares. In the meantime, the money that would have gone to taxes remains invested in the company, compounding year after year.

This leads to a strategic realization: Growth-tilted DGI stocks are often superior for taxable accounts, while high-yield stocks are best suited for tax-advantaged accounts like IRAs or 401(k)s. Ignoring this distinction can cost an investor hundreds of thousands of dollars in lost compounding over a thirty-year horizon. Masterful DGI strategy involves placing the right assets in the right “buckets” to minimize the friction of taxes on the yield-growth curve.

The Total Return Synthesis: Why the Trade-Off is a Spectrum

Ultimately, the Yield vs. Growth trade-off is a component of Total Return, which is defined as:

$$Total\ Return = Dividend\ Yield + Capital\ Appreciation$$

A common misconception is that dividend investors don’t care about capital appreciation, or that growth investors don’t care about income. In reality, they are seeking the same goal—wealth accumulation—via different mechanical paths. Consider two hypothetical investments over a 20-year period. Company A yields 4% with 6% annual dividend and price growth. Company B yields 1% with 9% annual dividend and price growth.

In both cases, the “expected” total return is roughly 10% per year. However, the experience of holding these two stocks is vastly different. Company A provides a smoother ride; the 4% yield acts as a “buffer” during market downturns. Even if the stock price remains flat for a year, the investor has still captured a 4% return in cash. Company B is more volatile; its value is tied to the market’s perception of its future growth.

The “Pillar” strategy recognizes that most investors need a blend. Pure yield-seeking can lead to stagnant portfolios that lose purchasing power to inflation. Pure growth-seeking can lead to “panic selling” when the market enters a bear cycle and there is no dividend check to provide comfort. By synthesizing both, the investor creates a “total return” engine that provides both current liquidity and future prosperity.

The following comparison illustrates the long-term mathematical reality of the yield-versus-growth trade-off, demonstrating how initial yield and growth rates influence the eventual size of an investor’s income stream.

| Metric | Strategy A: High Yield (Low Growth) | Strategy B: “Sweet Spot” (Moderate Growth) | Strategy C: High Growth (Low Initial Yield) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Initial Yield | 6.0% | 3.5% | 1.5% |

| Dividend Growth Rate | 2.0% | 7.0% | 12.0% |

| Year 1 Income ($10k inv.) | $600 | $350 | $150 |

| Year 10 Income | $731 | $688 | $465 |

| Year 20 Income | $891 | $1,354 | $1,447 |

| Estimated Portfolio Value | $21,000 | $46,000 | $67,000 |

| Final Yield on Cost | 8.9% | 13.5% | 14.5% |

Analysis: The Crossover Point

The table above reveals the “Crossover Point”—the moment when a lower-yielding but faster-growing investment begins to outproduce a high-yield laggard in absolute dollar terms.

- The High Yield Trap (Strategy A): While providing the most immediate cash flow, the 2% growth rate fails to meaningfully compound the principal or the income. By year 20, it provides the lowest income and the least capital appreciation.

- The Sweet Spot (Strategy B): This balanced approach overtakes Strategy A’s income by year 12. It provides a significant “middle ground” for investors who need current income but still want to see their wealth grow faster than inflation.

- The Power of Time (Strategy C): Despite starting with only $150 in annual income, the aggressive 12% growth rate allows it to become the highest income producer by the end of the 20-year period. This represents the ultimate victory of the “Growth” side of the trade-off.

International Considerations: Global Variations in the Trade-Off

The Yield vs. Growth trade-off is also influenced by geography and corporate culture. The US market is uniquely skewed toward growth and share buybacks. Many of the world’s premier “Low Yield, High Growth” compounders are headquartered in America, where the tax code and investor preference favor capital gains.

In contrast, markets like the United Kingdom, Australia, and Europe have a much stronger “Dividend Culture.” It is common for mature European companies to pay out a significantly higher percentage of their earnings than their US counterparts. In these regions, a 5% yield might be considered “normal” rather than a sign of distress.

For the DGI investor, looking internationally provides a way to diversify the yield-growth profile. An investor might find a “High-Yield, Low-Growth” utility in the UK to balance out a “Low-Yield, High-Growth” software company in the US. However, one must remain wary of “Withholding Taxes” on foreign dividends, which can add another layer of complexity to the trade-off. Diversifying across borders allows an investor to capture different economic cycles and different management philosophies regarding how capital should be returned to shareholders.

The Impact of Interest Rate Cycles

The Yield vs. Growth trade-off does not exist in a vacuum; it is deeply influenced by the “Risk-Free Rate,” typically represented by the 10-year Treasury bond. When interest rates are near zero, a 3% dividend yield looks like a gold mine. When Treasury rates rise to 5%, that same 3% dividend stock suddenly looks unattractive unless it offers significant growth.

In a high-rate environment, the “Growth” side of the trade-off becomes significantly more valuable. This is because high-growth companies can outpace inflation and the rising cost of capital. A static high-yield stock (the “bond proxy”) often sees its share price drop when rates rise, as investors flee to the safety of government bonds that offer similar yields with zero equity risk. Therefore, the Dividend Growth Strategy is a hedge against interest rate volatility. By focusing on companies that can grow their payouts, the investor ensures their income stream remains “relevant” regardless of what the Federal Reserve does. The trade-off shifts from seeking “maximum yield” to seeking “maximum spread” over the risk-free rate.

Behavioral Finance: The Psychology of the Trade-Off

Perhaps the most difficult aspect of managing the Yield vs. Growth trade-off is the psychological toll it takes on the investor. We are biologically wired to prefer a dollar today over two dollars tomorrow. This “hyperbolic discounting” makes high-yield stocks incredibly seductive. Seeing a large dividend hit your account provides an immediate hit of dopamine. It feels like “progress.” In contrast, watching a low-yield growth stock can feel like watching paint dry. An investor might hold a stock like Visa for five years, seeing a puny yield, while their neighbor brags about a 9% yield from a mortgage REIT.

However, the “growth” investor is playing a different game—the game of deferred gratification. The mastery of this trade-off requires the emotional discipline to understand that the Yield on Cost is the only yield that truly matters for long-term wealth. The psychological shift occurs when the investor stops looking at the current yield of the market and starts looking at the growth of their personal income stream relative to their initial investment.

Risk Management: The Payout Ratio as a Compass

The primary tool for navigating the risks inherent in this trade-off is the Payout Ratio. This is the percentage of a company’s earnings (or Free Cash Flow) paid out as dividends. In High-Yield Stocks, a payout ratio over 80% is a warning sign. It suggests the company has no room for error. If earnings dip, the dividend is the first thing to be cut. This is the danger zone of the trade-off.

In Growth Stocks, a payout ratio below 40% is a sign of immense potential. It means the company can double its dividend even if its earnings don’t grow at all. It represents a “coiled spring” of future income. By monitoring this ratio, the DGI investor can ensure they aren’t taking on excessive “Business Model Risk” in exchange for yield. A healthy portfolio balances “High Payout/Stable” companies with “Low Payout/Aggressive Growth” companies to create a resilient, self-correcting income machine.

Strategic Allocation: Building the Pyramid

A foundational Dividend Growth portfolio should be viewed as a pyramid. At the base, you want the Core Compounders. These are the “Dividend Aristocrats” or “Kings”—companies with 25 to 50+ years of consecutive dividend increases. They usually offer moderate yields and moderate growth. They provide the stability and the “floor” for your income.

In the middle, you place the Growth Engines. These are younger companies with lower yields but double-digit growth rates. They are the future Aristocrats that will drive the portfolio’s capital appreciation and long-term income ceiling. At the very top, in a small, controlled amount, you might have High-Yield Income Producers. These are included specifically to boost the current “blended yield” of the portfolio, providing cash that can be harvested or reinvested into the Growth Engines. By structuring the portfolio this way, the investor doesn’t have to “choose” between yield and growth—they own the entire spectrum, weighted toward the most sustainable path for their specific time horizon.

Conclusion: Mastering the Balance

The “Yield vs. Growth Trade-Off” is the definitive challenge for any investor building a Dividend Growth Strategy. It requires a sophisticated understanding of corporate finance, an awareness of sector-specific limitations, and the psychological fortitude to wait for compounding to work its magic.

The journey of a Dividend Growth Investor is one of constant recalibration. In your 20s, the “Growth” side of the trade-off is your greatest ally, as time is the multiplier that turns a 1% yield into a massive future income stream. As you approach retirement, the “Yield” side becomes more prominent, providing the cash flow necessary to sustain your lifestyle without being forced to sell shares during a market crash.

Mastering the balance is not about finding a magic number. It is about building a philosophy that respects the power of compounding while acknowledging the necessity of current income. It is the realization that a portfolio is a living ecosystem that requires both the “roots” of stable, high-yield companies and the “branches” of aggressive, high-growth firms. By applying the Chowder Rule, monitoring payout ratios, accounting for tax drag, and understanding sector and geographic dynamics, you move beyond the amateur pursuit of high yields. You become a sophisticated architect of wealth, building a foundational strategy that will stand the test of time, inflation, and market volatility.